Chippy Robinson: a Paratrooper’s story of escape after the Battle of Arnhem

© Peter Elliott 2019

Background

Sir Wilfred (“Chippy”) Robinson Bt (1917-2012) was a teacher at my school in Cape Town, South Africa and Chippy’s family have remained friends of mine ever since. At school we always speculated about Chippy’s war experiences and we knew he had been a paratrooper. He was a peaceable, reflective, person, and it was difficult to imagine him engaged in deadly war or a dramatic escape behind enemy lines.

Image 1. Officers Mess, 3rd Parachute Battalion-Pegasus Archive

Chippy is pictured second from the left, front row, in this detail from the group Mess photograph, taken at Spalding, Lincolnshire, in June 1944.

Chippy held the rank of Captain and was second-in-command of C Company, 3rd Parachute Battalion. This Battalion dropped at Arnhem on 17th September 1944 as part of the MARKET-GARDEN airborne offensive mounted in Southern Holland. Chippy’s Company made it through the Rhine Bridge area of Arnhem, and there the Company engaged in the fierce defence of the Limburg Van Stirum School building. The schoolhouse was under constant attack during the three day period during which the northern end of the Bridge was held by the Allies. [i] However this account does not focus on this episode: rather it is the story of Chippy’s subsequent escape, and draws on the full report he wrote about this experience for M.I.9.[ii] The author is able to give additional detail about the period during which Chippy and his American co-escapee were sheltered by Gert Spaan and his family. The current generation of this local farming family, still on the same farm, and descendants of the original farmer, who helped Chippy, have recounted their reminiscences.

Surrender at the Schoolhouse in Arnhem

By mid-afternoon of Wednesday 20th September the defenders of the schoolhouse in Arnhem had no water or food and virtually no ammunition. Since that morning artillery gunfire had started to blow away the roof and top storey of the school, and shelling had damaged the south end of the school. The Company commander concluded that the game was up, and he ordered the evacuation of the building mid-afternoon. Following a brief attempt to escape, Chippy and the others were all taken prisoner. The prisoners were transported to a hotel in Duiven and the next morning were taken by lorry to a POW Transit Camp one mile north of Emmerich, just across the border in Germany. There were about 60 Allied POW’s at this camp, including the new joiners.

During the evening of 21st September, Chippy and two American soldiers, Privates Matt and Esparza [iii] , managed to climb through a window into a roadway which passed along one side of the camp. The four steel bars set in lead in the window were loosened and pulled out by a Sapper, using Chippy’s escape file.

Chippy and his two companions walked across country in a north-westerly direction from the camp until just before sunrise on 22nd September. They then hid in a wood and separated, arranging to meet again at dark. In the early evening Chippy met up again with Private Esparza. They searched for Private Matt for a number of hours but failed to find him.

The two escapees then left the wood. They walked in a westerly direction until the early hours of the next day (23rd September) but made very slow progress, covering only three to five km. from the wood in which they had hidden, due to the swamps in the area. The men took cover in a clump of rushes and remained there until early evening when they again started walking west. They were making such slow progress that they decided to walk north to the railway and followed it through the remainder of that night. Early in the morning of the next day, 24th December, they approached a farm and hid in a barn. About an hour later they were discovered by a woman who called her husband. Chippy used his knowledge of Afrikaans (the dialect of Dutch spoken in his home South Africa) to inquire as to her nationality. She said she was German, but her husband was Dutch. The couple allowed them to remain in hiding in the barn until dark, and they were provided with food. Early that evening they followed the same pattern they had adopted on the previous two nights, and set out to cross country in the dark, and began walking north.

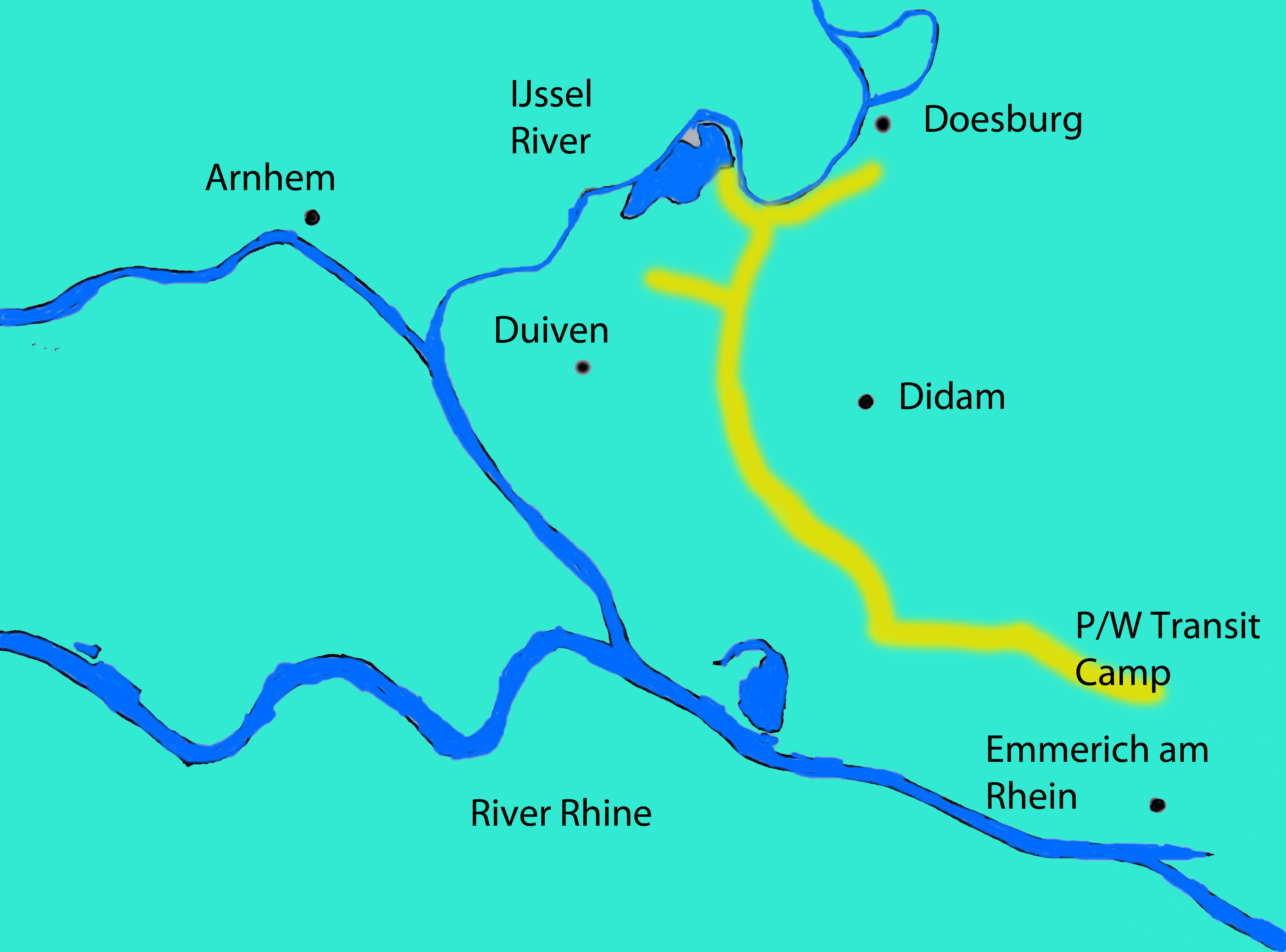

Image 2. Map of Chippy’s Escape Route: This is a rough attempt to track Chippy’s escape route (shaded in yellow). It is based on an interpretation of his account of the directions he and his American companion took at each stage of the escape, staying for protracted periods at two locations, including the farm of the Spaan family.

Well before break of day on the morning of 25th September they arrived at a farm about 3 km. south-west of Didam. They hid in a barn but were discovered by a workman. He told the owner of the farm, and there followed a discussion with the farmer, who agreed that they could remain there until dark. They were supplied with food, and that evening a former Dutch soldier arrived and guided them to the road leading north, giving them directions as to the best way to cross the river Lijssel. Again they walked through the night seeking shelter in a barn attached to a farmhouse before daybreak on 26th September. A few hours later they were discovered by two Dutch boys, who summonsed their parents who gave the two escapees food, and they were able to stay there until that night.

They then walked north and arrived near Bingerden, approximately 5 km. west of Doesburg. They searched for a boat to cross the river but were unable to locate one. The fugitives reached a farm before dawn on 27th September. Chippy’s written report is not explicit as to the location, and does not identify the people who helped him, but this farm is believed to be the one owned by the Spaan family at Rouvenenstraat, Duiven, where descendants of the farmer, Gert Spaan, still live today. Their own reminiscences about the escapees’ stay at the farm are detailed below. However, Chippy does say in his report that the two men hid in a barn and mid-morning they attracted the attention of the farmer, whom we now identify as Gert Spaan, who brought along a man who said he would establish contact with the Dutch Underground movement on their behalf.

That evening a Dutchman came to the barn with two pairs of overalls. The two escapees wore these over their uniforms and that night they were taken to a haystack about 400 yards from the farm. They remained there until before dawn the next morning, 28th September, when the Dutchman returned and directed them to another farm in the district, where they stayed during the day, and then were taken back to the Spaan farm at Duiven, staying there until the evening of 4th October. One can speculate as to why they were moved to another farm during that first day. However, based on the Spaan family account, it is fair to assume that Gert Spaan took the time that day to prepare a more-concealed hiding place in his barn (see below). The two men were fed and looked after by Gert Spaan, and his contacts, and kept in and around that same farm for a total of about eight days.

The Endgame of the Escape

On 4th October another farmer came to the Spaan farm and took the two escapees to a hut near Giesbeek, where they remained, and were fed, until about 10th October, a further six days. Here they were able to make contact with a number of other Allied soldiers who were hiding in the same district[iv] and also established communication with Major Hibbert of the Para. Regt., who insisted that they should stay where they were. This thwarted their immediate plan to try to rejoin their forces.

In the early evening of 10th October Chippy and Private Esparza were taken to a point on the river Lijssel north of Giesbeek. They travelled there by bicycle and were then taken across the river near Steeg. There they were taken to a house, where they stayed until late afternoon on the next day. Their guides of the previous day then took them to a cross-road, where they met two other Dutchmen. They had been on the run for a total of nineteen days and nights. For the first seven days and nights they had been on the move every night. Nowhere were they betrayed, but instead they were given sanctuary, and food, at no less than six different farms, at each of which they were either discovered in hiding, or revealed themselves. They were then given longer periods of sanctuary at the Spaan family farm at Duiven and in the hut near Giesbeek.

This is a story not only of the courage of a couple of escapees, but also of the Dutch farmers and resistance men who helped them along the way, taking huge risks themselves to help a couple of Allied soldiers. No doubt this is just one of many similar tales of the 300 survivors of Arnhem who evaded capture and returned to Allied lines. Help from the Dutch resistance was crucial in securing this outcome. The escape of the bigger groups of soldiers is well-documented. Some 138 such men crossed the Lower Rhine as part of Operation Pegasus I on the night of 22nd October. Chippy was one of these evadees who were “exfiltrated” out of occupied Holland that night (and this is consistent with the fact that we know that after reaching Steeg some 12 days earlier, following his own independent escape effort, the remainder of his journey was arranged for him).

Chippy was fortunate to have been able to leave Eindhoven for England on 24th October and to return to his regiment. His fellow escapee, American Private Esparza also returned to his regiment but was killed in action in the Ardennes only a couple of months later.

Eight Days hidden at the Spaan family farm: the family’s account

While he was alive Chippy Robinson, as is probably true of most of the participants, seldom spoke about his experiences at Arnhem.

In his last few years he did mention it more and more to his son but only to recount amusing memories of his actions during his escape – such as when he dropped his compass in the dark during the very first night of their escape, much to the annoyance of one his two co-escapees – and had to spend hours searching for it. The true story has only emerged much more recently, through a reading of his MI9 report, and discussions with the Spaan family who sheltered Chippy at their farm near Duiven.

Peter Robinson, Chippy’s son, accompanied his parents to the 60th anniversary celebrations in Arnhem in September 2004. His father had arranged for the Spaan family (who had looked after him during his escape) to accompany the Robinson family on a boat trip. The Spaans are mostly farming stock and speak little English but around 15 of them turned up and the families had a joint lunch. It was a very emotional reunion. One of the Spaan ladies had cycled 25 miles in order to attend.

During that visit Peter took his father into Germany where they briefly walked around the town of Emmerich, where he had been held prisoner before his escape.

When Chippy Robinson died at the end of 2013, aged 94, Peter Robinson wondered how to get in touch with the Spaan family to inform them about his death. He rummaged around his father’s documents and came across a receipt from Fortnums which had their address on it – his father used to send them a Fortnums hamper each Christmas, a tradition Peter has since continued.

In September 2014 Peter Robinson, his sister, and their family, attended the 70th anniversary celebrations (along with the author and his wife) and the highlight of the trip was another, very emotional, meeting with the Spaan family. There was a turnout of around 20 family members, the current generation of this family who had sheltered Chippy Robinson. The head of the family had, rather strictly, put a limit on how many family members could attend the lunch – but two Spaan ladies who were not ‘allowed’ to attend still made the trip to come and say hello before the lunch – very touching.

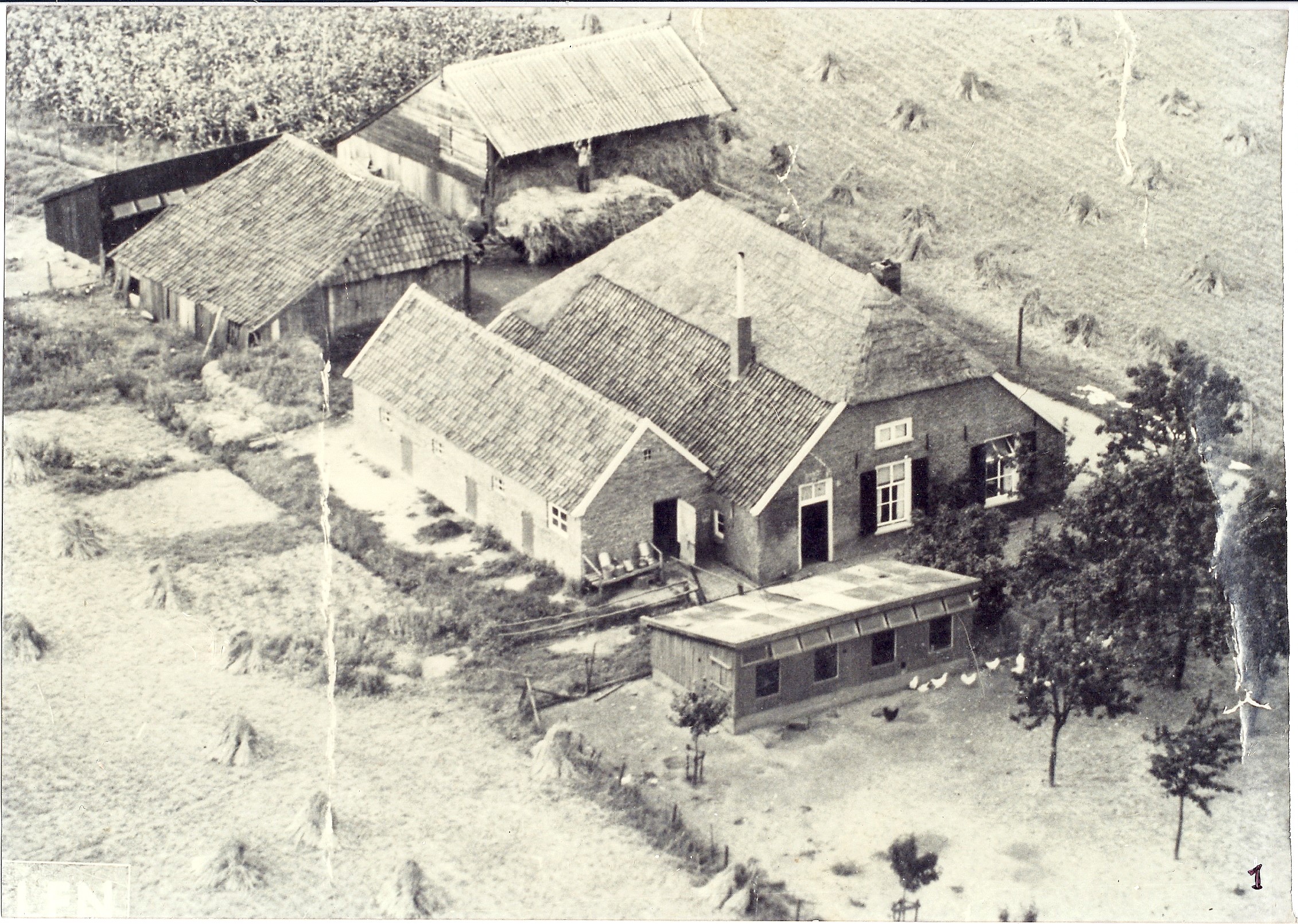

After lunch our whole party went to the farm, still owned by the Spaan family, where Chippy Robinson and his American paratrooper companion had hidden. At that time there had been a large German contingent camped literally over the road.

With hindsight it was either very brave (or foolhardy depending on how you look at these things) for the Spaan family to look after these escapees given the retributions that might have been visited on them had the escapees been discovered.

The story of Chippy’s concealment at the Spaan farm has since been supplemented by a couple of brief accounts in a book in Dutch concerning the German occupation of this part of the Netherlands, and also by stories that were able to be confirmed by Jan Spaan (born 1937) and Johanna Spaan (born 1940).[v]

The people of the communities of the Angerlo-Duiven districts were hugely courageous . After Chippy Robinson escaped form Emmerich, Germany , in the company of the Texan paratrooper Private Santiago Esparza, they were then helped by Dutch people to get to Bingerden. They were hidden in a stack of straw by D.W. Derksen in the Bingerden countryside. Derksen’s farm was near Angerlo and he took huge risks in engaging in this activity in that the Derksens also had Germans quartered at their farm. It was at Bingerden that Robinson and Esparza were provided with civilian clothes. A Benedictine Pastor Gerritsen and F.E.G. Waayen, a 23 year old young man, and Derksen himself all played their part in looking after the two escaped paratroopers. At that time the Benedictine priest, who was a member of the Dutch Resistance, lived at Klooster Bingerden, which was near the Derksen farm.

Jan Spaan (born 1937) confirmed that it was in fact Pastor Gerritsen who guided both Chippy Robinson and Private Esparza to the Spaan’s farm, near “Het Malland” on the boundary of the Angerlo-Duiven districts. Both men were taken over to the Spaan farm by day in civilian clothes, notwithstanding that the area was swarming with Germans and Todt workers (forced labourers, made to work for the Germans in occupied Netherlands).

The couple who owned the farm were Gerardus (“Gert” ) and Aleida Spaan (pictured below, before the war in 1935, and much later in 1960).

Johanna Spaan, the couple’s fourth child (who was 3 years old in September 1944), told of her memories of that moment when Chippy and his companion, Esparza, came and knocked on their door: her mother, Aleida, was very frightened when they arrived as she had been busy making butter from milk, whereas she was meant to hand over all milk to the Germans. So she had hidden all the butter she had made under the bed before she opened the door.

At the Spaan farm the two men were hidden in the old Barn.

As is evident from the photo the side of the barn facing the farmyard was open. The two paratroopers were hidden under a four-wheeled flat cart. The cart itself was surrounded by bundles of straw in order to conceal their hiding place under the cart and between its wheels. This space for them under the cart was only about 4 x 2 x 1 metres. The back entrance to the barn was also concealed on the outside by further bundles of straw. This secret back entrance then served to allow the farmer to access the hiding paratroopers without having to risk entering the barn from the front.

German soldiers were stationed in the barracks opposite the farm, and this was a mere 30 to 50 metres from the farm courtyard. However, fortunately there was a bend in the road and the barracks was not within the sightline of the open side of the barn. Nevertheless it remained risky, because the site of the barracks was quite close. As a matter of fact Gert Spaan kept on good terms with the soldiers in the barracks in order to be able to safeguard some of his illegal activities ( eg. illegal slaughtering of pigs and the transporting of meat in milk-cans). Spaan transported milk-cans to the milk-factory in Angerlo every day and this offered a good “cover” for his illegal pork activity, so for this reason he made it his business to keep on the right side of the German soldiers in the barracks. So much so that he permitted the soldiers to grow tobacco plants in the farm vegetable garden!

Gert Spaan became used to taking risks in order to help people whom he considered needed his assistance. His family described Gert as a typical “obstinaat” farmer. In principle he was not going to be downtrodden by the German occupier. He engaged in these illegal activities of killing animals simply to provide food for people in Arnhem who were short of food. So he had already put himself at risk. It was in this way that he was drawn into helping escaped allied soldiers.

Gert Spaan was, in fact, much more worried that a neighbour, who was a member of the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (NSB), the local Fascist movement, might get to know of the whereabouts of the two hidden paratroopers. This man had falsely accused Gert of some criminal activity, and this had resulted in his having spent a few days in Arnhem Prison, which had caused great strain to his wife who had to look after their five children while he was locked up.

The book Er op of er onder [v] also tells another anecdote of the time that Chippy Robinson spent hiding on the Spaan farm. One day during one of his walks over the farmland Gert Spaan found a boot protruding from a stack of seeds near his farm. He tugged hard at the boot but it was completely stuck and he could not shift it at all. He called out in his own dialect: “Come out. You can trust us here”, but this appeal produced no result whatsoever and he returned to the two Allied paratroopers hidden in his barn. Because Chippy Robinson spoke and understood Afrikaans (derived from an earlier Dutch dialect) he was the man with whom Gert Spaan could communicate and the three men returned together to the “living” seed stack. Robinson and Esparza then both tugged at the protruding boot, which they found again after searching in the seed stack, but they also had no success. Then the owner of the boot spoke in English, revealing himself also to be an allied paratrooper and a further paratrooper also appeared. Later it became apparent that these two had been looked after for some time at another farm. Again Mr A.G. Hopink, the director of the Tile Factory at Giesbeek, who worked for the Dutch Resistance, took them under his protection, and after a few days these paratroopers were able to leave the farm.

A further story is told about the last stage of the escape of Chippy and Esparza. They were taken safely over the IJssel River and they had to wait on the road below De Steeg together with their guide. A German army vehicle stopped in front of them rather suddenly and a tall German officer asked the guide the way to Zutphen. It could have been a disaster, but the guide kept cool, calm and collected, and quietly indicated the direction they had to take. The German army vehicle headed off as quickly as it had arrived.

The flat cart under which the two paratroopers had their hiding space in the farm barn, was displayed in the Liberation parade in Giesbeek after the end of the war. It bore the proud legend (in Dutch):Hier verborgen wij de parachutisten waar de Moffen niets van wisten (literally, It was here that we hid the paratroopers, such that the Germans knew nothing about them)

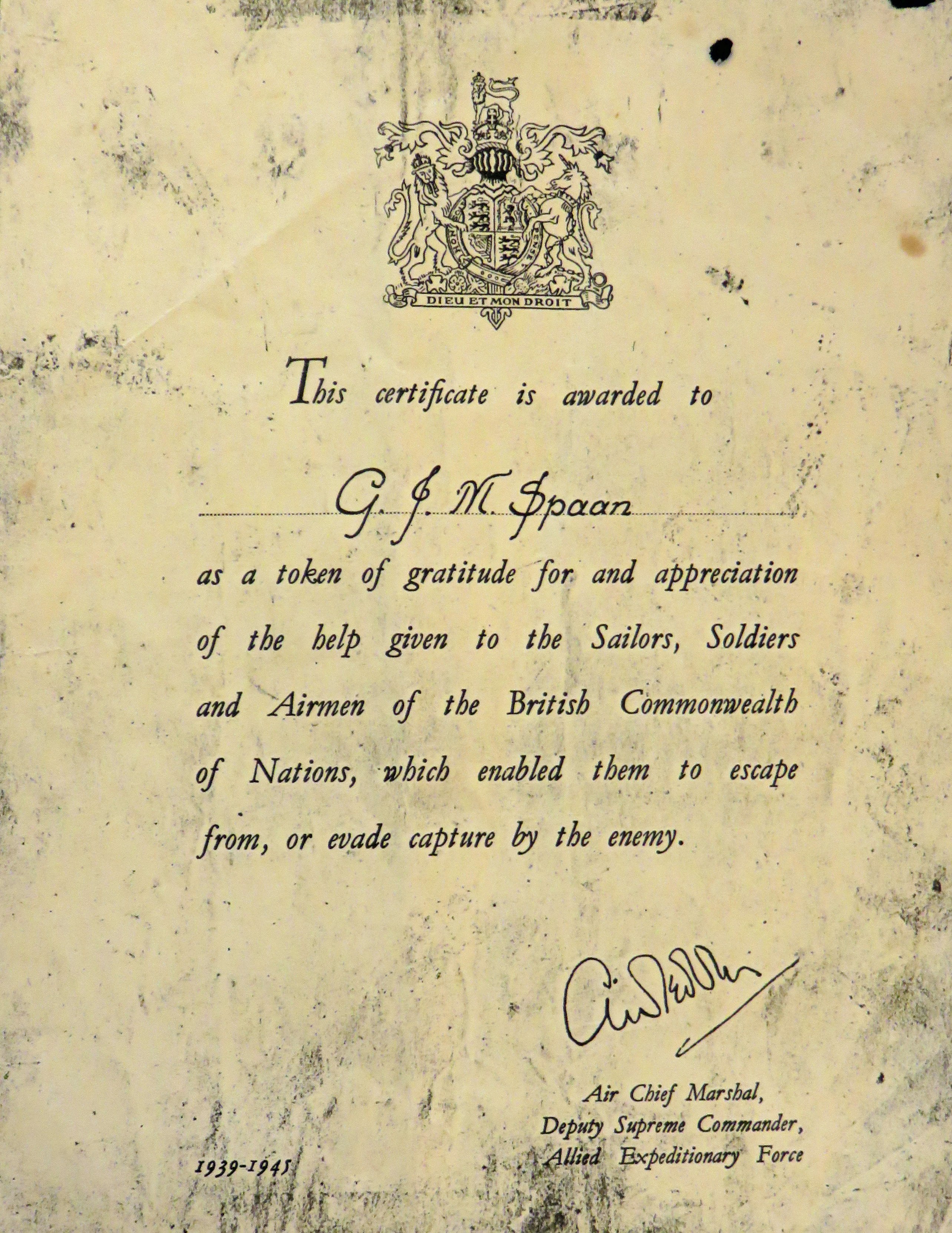

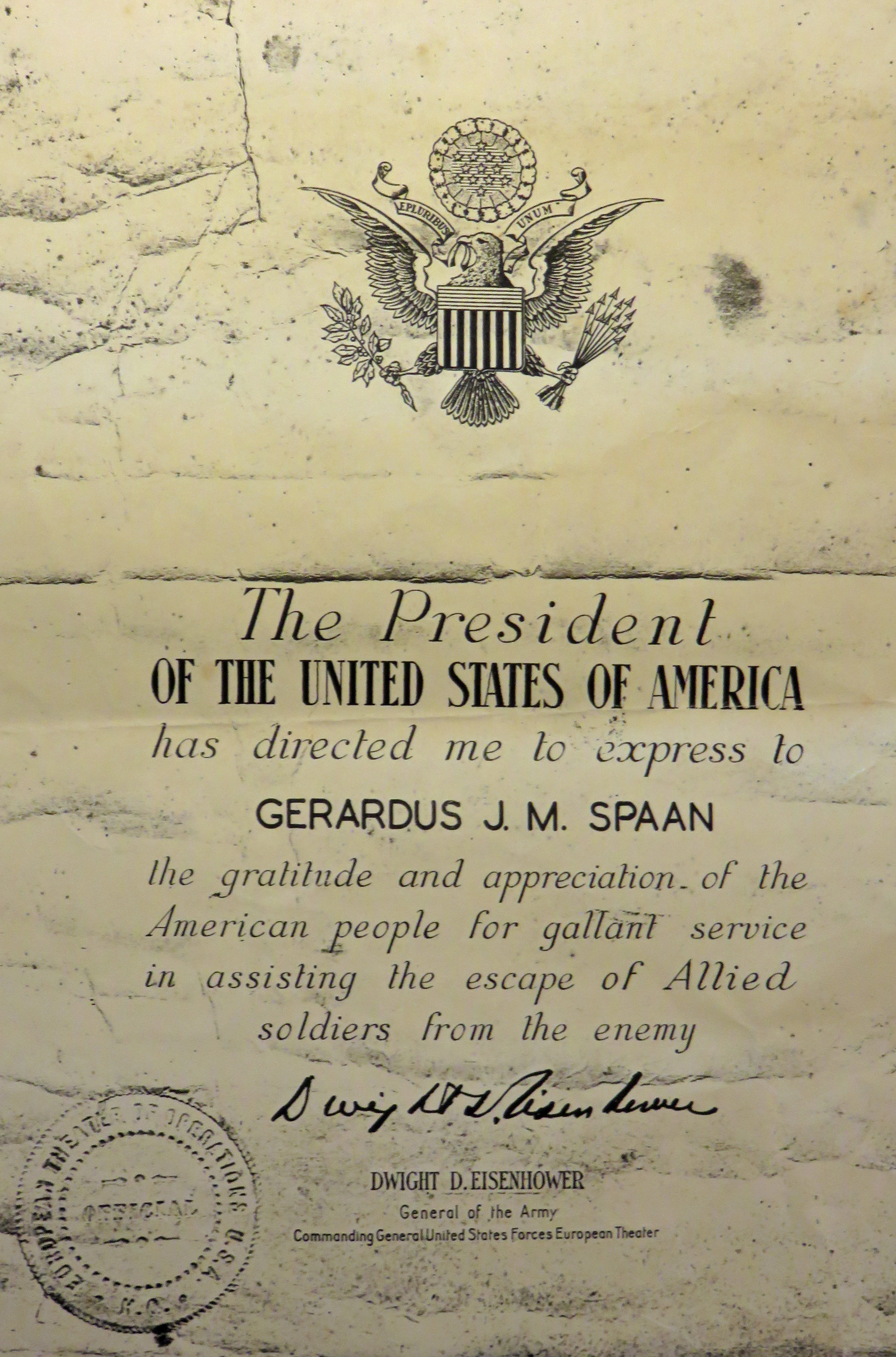

The descendants of Gert and Aleida Spaan still proudly cherish the certificates Gert received, both from the American and British government, recognising the help he gave to British soldiers enabling them to make their escape.

Peter Elliott grew up in South Africa, and went to school there, where he was taught history by Chippy. During his working career, Peter was a lawyer in the UK, but now lives with his wife in South West France, pursuing his interest in history. Apart from writing articles for journals, he has published three books, two of which have a Southern African Art History tilt. One of his books, Eight Months in the Veneto, is a story of British Liaison Officers who spent time with the partisans in the mountains of Veneto, Italy, in 1944-45. For more on Mr. Elliott, click here.

[i] The full story of the defence of the schoolhouse is told in the publication Arnhem Stories. Soldiers and civilians in and after September 1944, compiled by Geert Maassen for ABRG forum (2014): Chapter entitled Chippy Robinson: A South African at the Battle of Arnhem, by Peter Elliott.

[ii] Every British soldier who escaped from behind enemy lines was required, on his return, to make a report: Chippy’s own first-hand account of his escape after the Battle of Arnhem is contained in his report: Escape and Evasion Report of Capt. W.H. Robinson M.I.9/S/P.G./(G) 2870: National Archives Catalogue Reference WO/208/3325

[iii] The two American soldiers, Privates Matt and Esparza, were both of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division.

[iv] The others were: Privates Lorne and Ross, 156 Bn. Para. Regt.; Lieut. Hindley, Ist Para. Sqn,. R.E.

[v] The book is entitled Er op of er onder, Hoe Achterhoek en Lijmers de Duitsche besetting doorstonden en ervan werden bevrijd , verzameld door W.P. Nederkoorn and G.J.B. Stork , pages 365 to 366: The title literally means Make or break, how Achterhoek and Lijmers survived the German occupation and were liberated.